Shock is a condition of severe impairment of tissue perfusion leading to cellular injury and dysfunction. Rapid recognition and treatment are essential to prevent irreversible organ damage and death.

Different Causes And Categories Of Shock:

Hypovolemic shock

- Hemorrhage

- Intravascular volume depletion (e.g., vomiting, diarrhea, ketoacidosis)

- Internal sequestration (ascites, pancreatitis, intestinal obstruction)

Cardiogenic shock

- Myopathic (acute MI, fulminant myocarditis)

- Mechanical (e.g., acute mitral regurgitation, ventricular septal defect, severe aortic stenosis, aortic dissection with aortic insufficiency)

- Arrhythmic

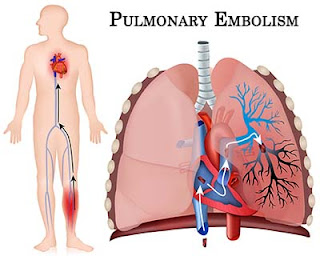

Extracardiac obstructive shock

- Pericardial tamponade

- Massive pulmonary embolism

- Tension pneumothorax

Distributive shock (profound decrease in systemic vascular tone)

- Sepsis

- Toxic overdoses

- Anaphylaxis

- Neurogenic (e.g., spinal cord injury)

- Endocrinologic (Addison’s disease, myxedema)

Clinical Manifestations:

• Hypotension (mean arterial BP <60 mmHg), tachycardia, tachypnea, pallor, restlessness, and altered sensorium.

• Signs of intense peripheral vasoconstriction, with weak pulses and cold clammy extremities. In distributive (e.g., septic) shock, vasodilation predominates and extremities are warm.

• Oliguria (<20 mL/h) and metabolic acidosis common.

• Acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome with noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, hypoxemia, and diffuse pulmonary infiltrates.

Approach To The Patient:

Obtain history for underlying causes, including

- cardiac disease (coronary disease, heart failure, pericardial disease),

- recent fever or infection leading to sepsis,

- drug effects (e.g., excess diuretics or ),

- conditions leading to pulmonary embolism and

- potential sources of bleeding.